R O U N D W E A T H E R

R O U N D W E A T H E R

Creative Reverence

December 4, 2020 - January 29, 2021

The six artists in Round Weather’s opening exhibition Creative Reverence are raising funds to temper the global climate crisis. The art of Colter Jacobsen, Terri Loewenthal, Brooks Shane Salzwedel, Andrew Schoultz, David Wilson, & Vanessa Woods can serve as tools for meditation and totems of aspiration as we live in the world as it is now, riddled with containment, excessive force, and irreparable ecological harm. Round Weather's Director and Advisory Council have selected Dogwood Alliance, Friends of the Earth, & Indigenous Environmental Network as our 2021 award recipients for their work mitigating climate change.

In a gallery with tone-setting guardrails made from reused on-site wood, Colter Jacobsen surveys found materials like reclaimed wood and an old book cover in place of canvas and paper. He lifts a trampled envelope and postcard of Yosemite from the street and into his watercolor regard. This tender, serene approach to an environment can also be secured by those who spend quality time with Jacobsen’s mandalas formed by cursive nows. Such pieces represent another thick thread throughout his art, love for the materiality of language. His illuminating, frequent work with nature is here evoked by traces of what grows around his home on a mountain in Ukiah, CA: a wild iris blocking darkness and oak gall ink making a resonant net from an Ohlone lyric, “Dancing on the brink of the world.” Jacobsen might be the contemporary artist to have most foraged visual recollection (via his preternatural memory drawings), and in a lecture at CSU Chico he says, “Remembering is the reverent awe and forgetting is the exploitive use,” adding remembering and forgetting to historian Kevin Starr’s diagnosis of nonindigenous Californians’ uneven frame of mind.

David Wilson also utilizes remembered resources and materials. Both of Wilson’s canyon works in Creative Reverence are framed in doubly-reused old-growth redwood he originally collected from a salvage yard to build the frame for his massive drawing Frog Woman Rock, temporarily placed in the Presidio by SFMOMA in 2013. Wilson’s frames thus become sculptures and tree-hugging emblems. They surround melodious sumi ink paintings that mark a major development in his plein-air practice. Known for landscapes gesturally concentrated onto small paper or grandly assembled from myriad days of hand-held, place-held drawings, here Wilson scales up his surfaces. Canyon receives a full-bodied rendering that includes the artist’s shoe prints as he strives to keep the painting plane still. Feb 6, Claremont Canyon, for Paul—dedicated to the memory of visionary Paul Clipson—subsumes built environments in favor of feelings the environment builds, emerging from what Wilson calls spirit-time. In a recent essay Wilson writes, “Spirit-time is a creative engagement with time, an effort to move towards experiences that remind us of wonder and keep us open to the unknown.”

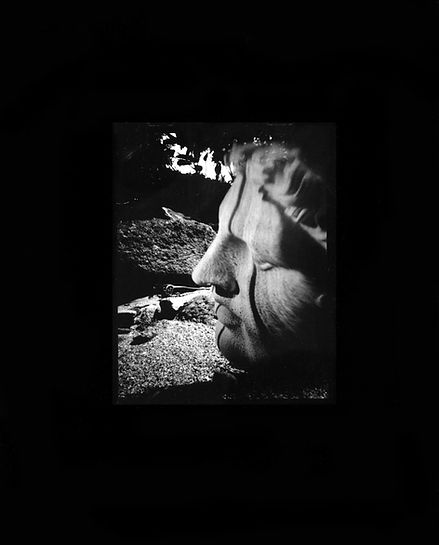

Terri Loewenthal, with Jacobsen and Wilson, is the exhibit’s third artist to have given spirit-time to land in Ukiah, CA, which suggests the scent of an artistic movement, less of stylistic consistency and more of open-ended collaboration with the natural world in Northern California. Also Loewenthal photographed portraits of contributors—including Jacobsen—to Wilson and Lawrence Rinder’s The Possible at BAMPFA, a generative exhibit that alchemized gallery spaces into workshops where piles of woodsy artists and the public created together. Her Psychscapes series of wildly contemplative single-exposure photographs search out their effects in camera using optics hand-crafted by Loewenthal. They help enact the undulation between observer and observed. Recent books The Overstory and The Hidden Life of Trees popularize contemporary science that has begun to realize how trees communicate across distances. Similarly, Loewenthal’s high-hued photography rides the ways various elements in an environment seem to speak among themselves, sending unnamable word to her. There is brought here, over is wrapped under, rock becomes cloud, sharp and soft focusses gel until our eyes pulse with place. We become a grateful figment of where we are.

As Loewenthal pictures a unifying plane, Vanessa Woods unveils her pinhole photographs, their boundless depth of field holding everything in focus and “collapsing,” to quote Woods, “what is fact and fiction.” Pinhole photography is a marvel of nature and the origin of an art form. Round Weather is honored to show how Woods, noted as a virtuoso of collage and bodily celebration, also photographs collage constructions, which include mothering anatomy, crumbling empire statuary, and deep-focus psychology embedded in conversation with physical environments. In a lecture at the Missoula Art Museum, Lucy Lippard talks about her book Undermining, saying, “There’s a point where artists like everyone else have to take some responsibility for the places they love, a point at which the colonization of magnificent scenery gives way to a more painfully focused vision of the fragile landscape and its bewildered inhabitants.” Woods’ work painfully spreads the focal point of fragility across bodies, cultures, and landforms throughout California—the High Sierras, Mojave Desert, Pacifica, Sutro Baths—earth uprooted and sky downsized into elements of collage with human expansion and ruin. The balm is that her compositional derring-do always uncovers beauty too.

Andrew Schoultz’s paintings have climbed the walls—from street art murals and into the collections at SFMOMA and LACMA. The most gifted patternist to have made a splash in San Francisco’s Mission District, he now lives in Los Angeles. His optically and mythically mesmerizing work is heavy with bird, beast, and serpent. Oceans revolt and weather addles his retinal-blast animals; clouds—or is it smoke?—get all up in everything. This great gobsmacking can inspire despair or awaken environmental action. His beasts all but ask, “Which side are you on?” while the human-made bricks and vase and the vast hand acknowledge we’re all inside the structured mess. Schoultz’s profound design sense and his one-dollar-derived eyes in the sky point to an unsettling reverence for poetic justice. The tensile brushwork in his figures and grounds and the motion of the Biblical creatures—with their cartoonish articulation of dead-serious subject matter—all gather force and torque to depict a powerfully irreverent spirituality.

Brooks Shane Salzwedel is also given to paradox. Round Weather is thrilled to include works from this Los-Angeles-based artist's Contained series, where shapes evocative of edifices (both high-rises and concrete foundations) enclose delicately delivered forests. The woods still find a way to poke—but not break—out. A Building, Ghosted forms a Mobius-esque effect where the Contained motif is both inside and around the natural world. Salzwedel’s graphite trees and hushed colors appear depressed, long-charred, winterized. His mylar- and resin-induced atmospherics capture the mood most enter when they think about climate change: haunted by the future, already here and now. Like Woods, he still remains attentive to and inventive of loveliness. Salzwedel’s images gather growing seeds of light, offering aesthetic sustenance and faint hope to viewers. His bare tree branches against stark backgrounds resemble nervous as well as vascular systems, which feels totemic of the nondual spirit with which Lippard writes about the climate crisis in Undermining, “My guiding light for many years has been Antonio Gramsci’s stirring call for pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” Round Weather also answers such a call.

Preview:

Colter Jacobsen

courtesy of Anglim/Trimble, Callicoon Fine Arts, Corvi-Mora

Penumbra (Wild Pacific Iris), 2018, ink on paper, 14 x 8 3/4 in.

Terri Loewenthal

courtesy of CULT | Aimee Friberg Exhibitions, Galerie Hug, Jackson Fine Art

Psychscape 16 (Lassen, CA), 2017, archival pigment print,

edition 1/5 + 2AP, 40 x 30 in.

Brooks Shane Salzwedel

courtesy of Johansson Projects

Greenhouse Sunset, 2017, graphite, ink, tape, mylar, thread, 17 x 12 in.

Andrew Schoultz

courtesy of Hosfelt Gallery

Swimming Beast (Vessel), 2017, acrylic on canvas on panel, 30 x 22 in.

David Wilson

Feb 6, Claremont Canyon, for Paul, 2018, sumi ink on paper (artist built frame), 61 x 99 in.

Vanessa Woods

courtesy of Jack Fischer Gallery

Nothing Beside Remains, 2018, silver gelatin contact print from pinhole paper negative,

edition of 8, 8 x 10 in.